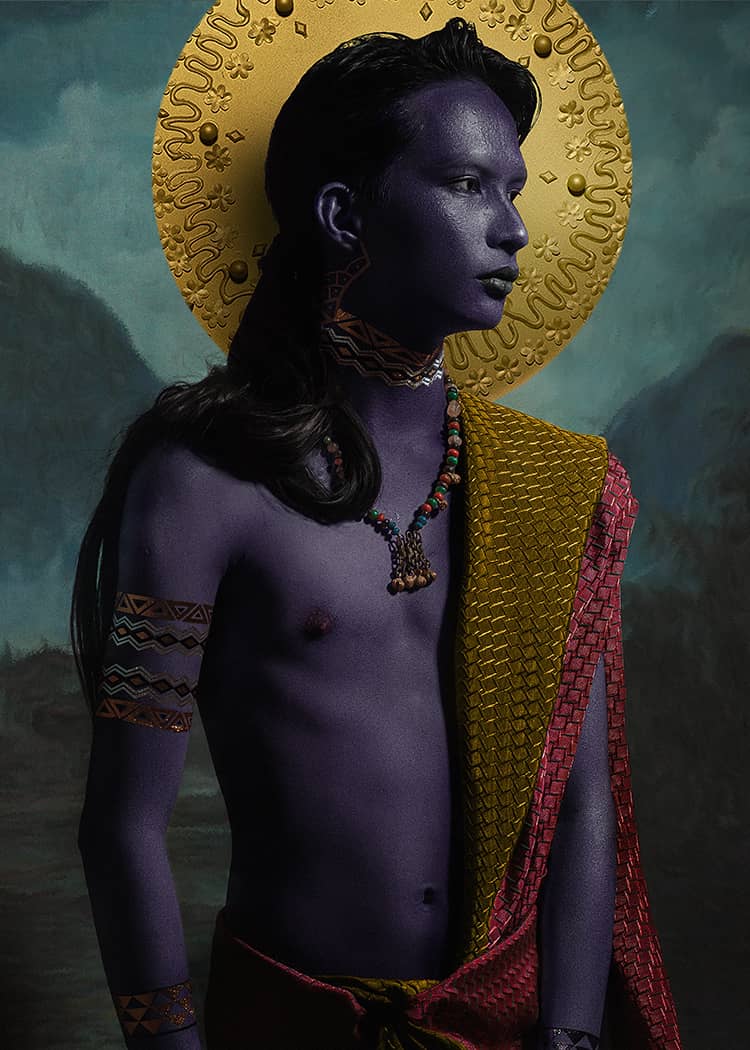

Ikapati or Lakapati

According to fragments of myths that have survived, Creation was conceived by the goddess Ikapati. One day, she saw her consort, Bathala, wandering alone across the Cosmos. To amuse him, Ikapati gave Bathala clay from which he fashioned a ball that became the Earth. Upon the surface of this ball, he created rivers, oceans, mountains, and forests. Pleased by her husband’s creation, Ikapati hung the ball up in the sky so they could both marvel at its grandeur.

Ikapati was an important deity to the Tagalogs. As the goddess of agriculture, she was worshipped as the great provider. She was also the Mother Goddess who kept her children safe from harm and who healed them when they fell ill. Though, most importantly\notably, she was a transgender goddess. The myth of Ikapati is evidence of how our ancestors in pre-colonial Philippines celebrated gender variance. The science writer Deborah Rudacille emphasizes that gender-crossing is ubiquitous across cultures; the genitalia, as it is, is not a distinguisher of gender.

Bulan and Sidapa

Long ago, at the summit of Mount Madja-as in Panay, Sidapa the God of Death became captivated by the dance of the seven moons and fell in love with them. Upon realizing that other gods were similarly besotted, he commanded the birds and the mermaids to sing songs to the moons. He made the flowers bloom so their sweet perfumes reached the heavens. He then asked the fireflies to light the way to his mountain. The boy Bulan, the youngest of the moons, came down, and Sidapa showered him with gifts of gold.

One night, the great dragon Bakunawa, who was also besotted by the beauty of the moons, rose from the sea to devour them. As soon as he learned of the attack, Sidapa flew to the heavens, snatched Bulan, and brought him back to Mount Madja-as. It is believed that, until this day, they still live on top of the mountain as lovers.

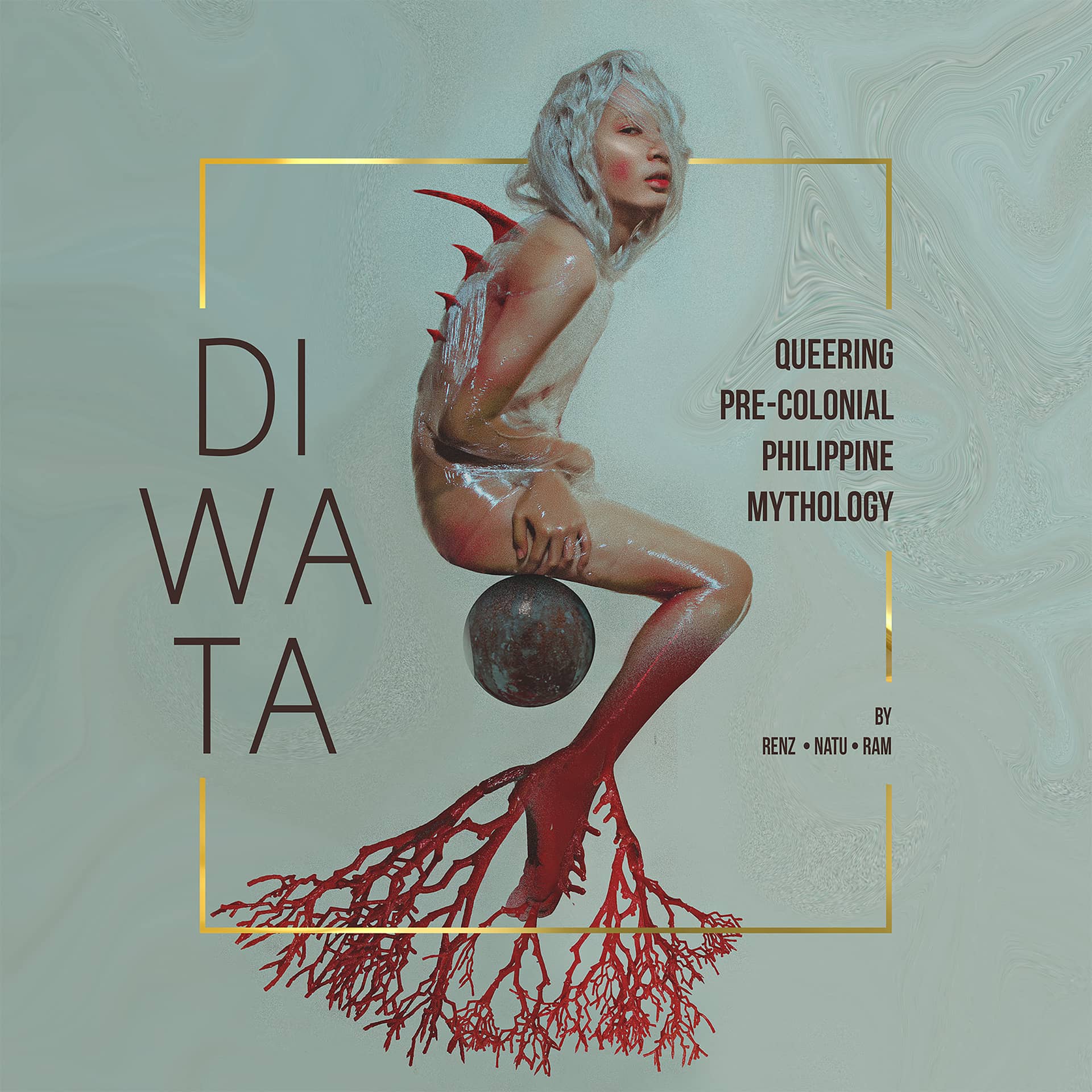

Sirena

Various iterations of mermaids exist in Philippine myths. In Bicol, they are called Magindara, guardians of the sea, though they are also believed to prey on humans. The Sama Dilaut believe mermaids to be omens of catastrophe, while the Manobos who dwell at the foot of the Pantaron Mountain Range call them Alimugkat, guardians of the great rivers. The Alimugkat have silver hair and colorful scales. In a tale told among the Manobos, Alimugkat was the youngest of eight siblings and the only female. When her brothers insisted upon setting out on a quest to conquer the most dangerous mountain of the Pantaron as a rite of passage to adulthood, she warned them of the human-eating Busaws who dwell there. But the brothers would not listen to their little sister. After a time, as her brothers had not yet returned, she took it upon herself to rescue them. When she reached the dangerous mountain, however, she only found her brothers’ remains; they had all been eaten. She gathered up their bones and used her power to restore her brothers back to life.

The mermaid is an important figure for trans women. With the upper body of a woman and the tail of a fish from the waist down, her womanhood and femininity are not defined by what is between her legs (after all, she has none). A children’s book by Jessica Love, Julian is a Mermaid, is about a transgender child who wants to be like the spectacularly dressed women she meets in the subway. Jung calls these archetypes, or alternatively the model role figures incarnated as characters in myths. These archetypes are part of our collective consciousness and they inform us of meaningful symbols from the moment we are born into this world.

Nagmalitung Yawa Sinagmaling Diwata

Nagmalitung Yawa is one of the three powerful sister-goddesses of the Hinilawod. She is a binukot, that is, according to Hiligaynon practice, a noble woman who is kept away from sunlight and the outside world. During her time as a binukot, Nagmalitung Yawa studied witchcraft and she was revered and feared both as a protector goddess and a demoness.

When the hero Humadapnon was captured by the goddess Lubay Lubyok Mahanginun si Mahuyokhuyokan and her army of women warriors, his men sought the help of Nagmalitung Yawa, for only a powerful goddess could rival another. Nagmalitung Yawa agreed to help but she worried that to be saved by a woman would hurt Humadapnon’s fragile masculinity. So she turned herself into a man and called herself Datu Sunmasakay. This act of transformation or duality is similar to Hindu mythology; for instance, the god Vishnu took the form of the goddess Mohini to seduce the destroyer Shiva. Since many parts of the Visayas and Mindanao were once Indianized kingdoms, it is no surprise to see such influences.

Oryol

According to the folk epic Ibalong of Bicol, Oryol was a beautiful princess who was cursed by a jealous sorceress and turned her into a snake woman. She became the guardian of the forest and her horde of monsters. The hero Hadyong, determined to conquer the forest, waged a fierce battle against the monsters. Yet he was seduced by Oryol, who had turned herself into a beautiful woman. Just before she was about to kill him, she turned back into a half-snake, but Hadyong was too quick; he grabbed Oryol by the throat and began to choke her. On the verge of death, she turned once more into a beautiful woman, and Hadyong could not bear to kill her. A man in love, he kissed Oryol, and the cursed pitogo seed that bound her fell from her hands and she was freed.

The myth of Oryol is similar to several myths about half-woman, half-snake beings, such as the tale of the White Snake from China and the Arabic tale of the Laughing Snake. The latter is referenced by the artist Morehshin Allahyari in her project She Who Sees The Unknown to explore, as the Whitney Museum puts it, “personal and imagined stories to address topics such as femininity, sexual abuse, morality, and hysteria. The snake emerges as a complex figure, reflecting multifaceted and sometimes distorted views of the female, and refracting images of otherness and monstrosity.”

Makapatag-Malaon

Makapatag-Malaon is the supreme deity of the pre-colonial Waray society. Unlike the gender-ambiguous creator Bathala of the Tagalogs, Makapatag-Malaon is both man and woman simultaneously. The fearful and destructive aspect is attributed to the male, Makapatag; the gentle and understanding aspect is attributed to the female, Malaon. Again, this is an apparent Hindu influence of the duality of the divine — the world depends on the union of Shiva and Parvati as they maintain the equilibrium between the ethereal and the material.

Babaylan In pre-colonial Philippines, one of the pillars of society was the Babaylan. As a priestess, she held comparable societal rank to the Datu and the Bagani. Only a woman (cis or trans) could become a Babaylan. It is argued that, in pre-colonial Philippines, and still in some indigenous communities today, gender was determined not by the genitalia but by one’s social contribution. When the Spaniards came, they refused to accept such a concept of gender. Instead, they insisted upon their violent colonialist worldview. They controlled how we think, vilified our myths and lore, made Babaylans into frightening witches, and massacred them. They tried to suppress transgender people and removed us from our rightful place in history. We have been made to believe that transgender people and genderqueers are spawns of the devil, an abomination of nature. But we have always been part of this country’s history. Always.

The American anthropologist Stuart Schlegel was initially perplexed when he met a mentefuwaley libun (transgender woman) from the Teduray community; she was a celebrated zither player. When he insisted that she was a man, members of the community corrected him and firmly asserted that she was no less of a woman than the cisgender women within their community.